Letter: Grounds for Divorce

One reader has a novel recommendation for resolving Rowan and Glassboro's conflicts.

Views expressed in letters to the editor do not represent the opinions of The Gaffer, its staff, or the editorial board. The following was edited for brevity and modernity. Links and images were added for context.

He had now entered the skirts of the village. A troop of strange children ran at his heels, hooting after him, and pointing at his gray beard. [...] The very village was altered; it was larger and more populous. There were rows of houses which he had never seen before, and those which had been his familiar haunts had disappeared. Strange names were over the doors—strange faces at the windows—everything was strange.

—From Rip Van Winkle

My past letter left off at the parking problem which plagued my nephew and I prior to us finally entering that new café in Glassboro named ⸻.1 I apologize again for my great delay in concluding this story, but I needed time to process what I experienced that day. It seems, however, that one lifetime wouldn’t be enough and, in the interest of telling the public what I saw before my little time left expires—though part of me desperately wants to let this information go with me—I hastily edited the following, written in fragments throughout the year.

Nestled on a corner of High Street once productively employed by an insurance concern, then left to languish as this historic downtown declined and Count von Rowan rose, the space was recently renovated in a sawmill chic fashion: wooden planks hanging from the ceiling, exposed HVAC ducts and electrical wiring, the bar made to look like it sits atop a great hewn tree trunk, things of this nature. But garishly large windows expose this industrious design as a mere staging area for the indolent horde encamped within.

Upon entry, my nephew scurried off to reserve us one of the leather sofas—which he insistently called “the casting couch” throughout our visit, perhaps in reference to some understaffed theater troupe he’s involved with, though I have never known him a thespian—with an aggressive plop of knapsack upon well-worn cushions. He then directed me toward a great menu scrawled upon yonder wall. Etched in hipster hieroglyphics were, I must assume, the names of drinks favored by the 25.000 petty student monarchs ruling over Rowan’s conquered kingdom.

The tattooed coffee maid beckoned us, and my nephew—after a gruff greeting, skipping the common pleasantries of asking how one’s day is going or telling the maid how handsome she is—relayed a lengthy order that might have jangled my nerves. But simple Swedish coffeehouses are distant cousins to these post-modernist cafés, so with genetic memory I requested a mere cuppa. After a cranking of the cogs behind our astute server’s eyes, she seemed to catch my drift, but not before offering me a plethora of ultra-processed additives (pasteurized milk, refined cane sugar, ice) which I duly denied. We paid a usurious price, then at last retired to the sofa.

As we settled, our gaze naturally fixed upon the Garden of Earthly Delights before us. At the far end of the room sat a small stage with scarcely space enough for—I must presume, on event nights—a bare-bones jazz band (yet another symptom of Glassboro’s urban transformation), but which now held another sofa. Between us and the stage exhibited a menagerie of tables set with scores of scapegrace students. Gangs of lads crowded about, imbibing caffeine in preparation for no activity in particular; flocks of girls gathered in gossipy covens paying unholy homage to flutes of false, sugary bliss; the sexes intermingling freely in affront to even a threadbare upbringing. But the most wretched souls sat against the windows, scrunched and dead silent side-by-side at one tall, long table, clacking away at greasy button-boxes in droll pantomime of productivity, lest they engage meaningfully with their fellow man just beside them.

A great hallooing echoed from the bar, and my nephew fetched our drinks. Miraculously, my coffee seemed correctly constructed, though it bore no notes of the veritable history-in-a-cup served just around the corner at Angelo’s. Our conversation then turned, inexorably, to national politics. But just as I was regaling my nephew with, in my estimation, the relative merits and demerits of New Jersey’s likely candidates for our 2028 presidential electors…

My eye stole a closer look at one of those poor creatures adorning the window table. Stooped over their computer, eyes unblinking, nursing their mug with newborn zeal, yet something was off about this one. I thought I couldn’t quite put my finger on it, but that was just it, their fingers were unnaturally long, chittering like a cricket’s legs—perhaps even bending at one more point than human digits might, though given their speed I couldn’t be sure.

For the sake of propriety or my sanity I averted my gaze to the back of the room. An unwise choice. On the stage sofa sat a lone person, I was sure of it, but they were obscured, as if I wasn’t wearing my bifocals. Queerer still, every one and thing else around and in front of the stage came in clear. I tried to focus on the fellow, risking rudeness, going so far as to remove my glasses, hold them up, and peer into them so as to magnify this figure, but all for naught.

Just then, the man—at least, as I could tell—stood up, no clearer still. My head turned away of its own accord, and I felt grateful to it, not just to save face, but for another reason I could not yet grasp. My attention should have turned back to my poor nephew, who must have been in tatters over his uncle’s state, but… there was something profoundly alien about the couch man, much too tall, out of proportion, a long upper body tethered to legs half its length. I dared not consider this further.

After two uncanny observations in a row I sought the solitude of my cup, to stare down into the inky abyss, breathe deeply its bitter cleansing breath.

I thought I heard a sound. Some uneasy thrumming barely there, perchance not. I would have wanted to search the bedlam ahead for its source, but my eyes could only focus upon the mug at hand. A deep black sea sat silently therein, already cold, free of crest or current, dead still beneath a dying sun in an otherwise starless sky. I scanned the horizons for land, but I knew there was no such thing. This planet died eons ago, lost in a lonely galaxy, core snuffed out, mountains ground to sand long settled down impossible depths. Not a soul lives here. Not a sound. Only my own ears’ tinnitic chiming to ring in oblivion, the waning light to show me where the water ended and the long night begins.

I strained to hear any thing at all, but I did not like what answered. That low hum from before—all my brief life a mere unpleasantness banished to the back of my mind—came to the fore. I searched again in vain; I was truly alone. The sound grew to an unmistakable whisper licking the sea’s surface. I thought then of my nephew: where was he now, and what evil had befallen him that spared me only for what worse fate? Louder still, now a phantom laughter ringing out across the endless expanse, in all directions, circumnavigating the planet, overlapping itself, looping over and again into an incomprehensible babble—still muffled, as if some thing stood just behind a door, waiting patiently for me to open up. Waves of existential pap rolled over me, battered me in bleak crescendo. I screamed! desperate to remain conscious against a cacophonous call-response that would drown me. Bleak currents deep within me stirred up millennial detritus long suffocated beneath one billion billion grains of ground memories.

Seeking inner peace, I covered my ears and closed my eyes. I saw the handsome cashier, the canoodling patrons, my estranged niece—the ex-wife had gotten her in the divorce—my dear nephew, who stuck by me, now lost; the sum total of all Lindens who ever lived, going back to the Garden of Eden. Their eyes were closed. All were flotsam floating limply in a black sea, mouths agape, humming, an idiot choir ululating the inevitability of it all.

How long had I been there? Had I sat out the remainder of all time? Had I outlived anyone I had ever known or could know, all whom I loved or could love me? I had run out, I felt it now, the weight of the universe collapsing into me. All corners of space racing at an exponential rate toward this singular point wherever I was, the great convergence where all would be one again. Perhaps she would come back to me, but then there would be nothing again.

Exhausted, I opened my eyes to face this thing. Silence. I saw black stars for the first time. I was all who was left. Only I could see them. I was left.

I was back on the casting couch with my nephew, and it somehow seemed as though our conversation had not lapsed at all. He was expressing confusion at my deep conviction that Middlesex County Republican Chair Robert Bengivenga doesn’t deserve the 2028 Electoral College ticket, that he’s as faithless as a Calvinist. Shaken, realizing only a glimmer of the profundity of what I had just seen, the cosmic implications and there being no coincidence that I should experience it here in this den of infamy, I put on as brave a face as any man might have mustered, and turned us to other matters: namely, Rowan’s exponential growth and encroachment upon every aspect of lifelong residents’ lives. I shall paraphrase my points here:

One may view Rowan University and Glassboro as partners in a troubled marriage. Long ago, we shared values, mutual respect, and a sense of purpose. But time and money matters changed us. Our interests drifted far apart, though we must remain in close proximity. Inevitably, we clash. One partner’s growth becomes the other’s noise complaint. One yearns for old-style simplicity, yet the other seeks the pleasures of the city. One spends her days scrolling the Facebook groups, the other perhaps pouring over literal scrolls in his study. In the end, one must be freed of the other. It won’t be easy; decades of devotion don’t so easily dissipate—no matter how much one partner may insist otherwise. It won’t be pretty; friends and relations will inevitably take sides; while I can always rely on my loyal yet soft-headed nephew, I lost my headstrong niece in the Faustian bargain. And though one side may initiate divorce proceedings unilaterally (such is the state of justice in what’s become of our country), it may actually be the case that the other side, in fact, was the first to choose to leave but was too occupied with other matters to initiate, myself. In any case, when the dust settles, both parties shall be better off. I, for one, am completely content now. But I digress.

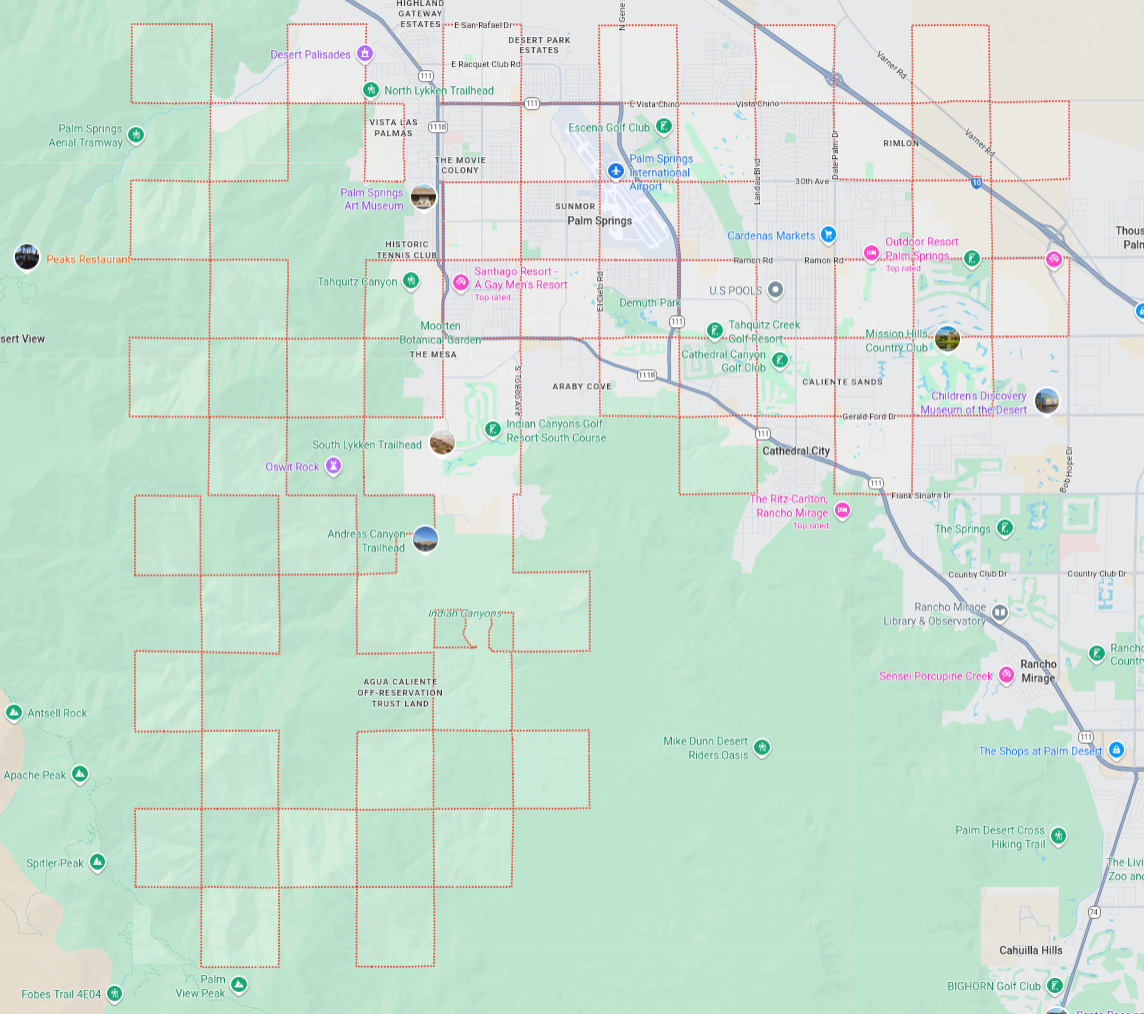

I recommend that Glassboro force Rowan to secede its campus and closely linked environs—Rowan Boulevard, Fraternity Row, affordable housing developments, cafés, et cetera—to incorporate its own municipality of Rowanville, thereby making de jure what’s long been de facto. The result may very well be an awkward patchwork of jurisdictions akin to how some native reservations are knitted into settler towns. [Editor’s note: See the Agua Caliente Indian Reservation below.] To prevent spillovers of crime, noise, and merriment from this new neighbor into our newly liberated Glassboro, and to allow Glassborons to travel about without passing haplessly through Rowan country, a network of fences and underground tunnels may be necessary. Nevertheless, all parties will in the end come out of these proceedings better off. Trust me.

Especially so for the good citizens of Chestnut Ridge—some no doubt descending from those quiet Quakers who managed to hold their ground against successive assaults from the likes of Carpenter and Heston, then Whitney and Whitney, now Count Rowan and King Wallace III—who are doubtless in a continual state of existential despair by a looming threat: the noxious fumes and harum-scarum activity emanating from these new businesses satisfying student whims at the expense of lifelong residents, establishments such as this café ⸻ which I dare not enter again.

Cade Linden, Swedesboro

Editor’s note: Business name withheld.